SCREEN DIARY: WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER

RADIANT CIRCUS went to the UK premiere of Amos Gitai’s WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (23 NOV 2017). Here’s our writeup.

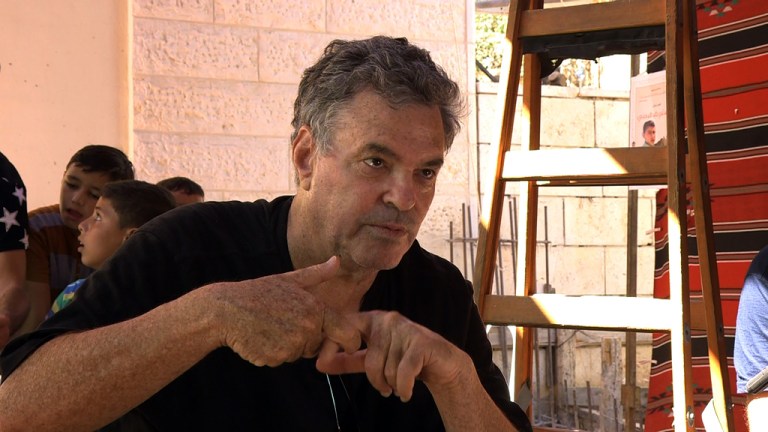

RADIANT CIRCUS went to the UK premiere of Amos Gitai’s latest documentary WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER at the ICA (23 NOV 2017). Marking Gitai’s return to filmmaking in the occupied territories after a break of 35 years, ICA’s Nico Marzano asked the director why he’d taken so long: “No reason is more powerful than a reason… There is no momentum”.

WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER – presented as an update to Gitai’s 1982 film FIELD DIARY – looks at what has changed in Israel’s political class since the 1995 assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. It also reveals how Israeli and Palestinian citizens are working together to create their own quiet force for peaceful coexistence in the absence of political will.

“If you say something true it will be revealed”

Shot mostly matter-of-factly, WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER is bookended by two startling symbols of perpetual motion. The film opens with a young Palestinian boy trying to sell strawberries to passing traffic at a busy border crossing. Rebuffed by driver after driver, he occasionally stops to look into the camera as if to ask “should I keep going?”. The film’s final sequences intercut footage of a bustling community backgammon competition and a silently observed image of a mother and child riding a revolving but otherwise empty carousel.

Frustrated with decades of such futile spinning, Gitai clearly despairs of a global political class that is now more enamoured with entrenched positions and soundbites than the inevitably painful process of working towards peace. Praising Rabin’s “simplicity” in speaking from the heart, Gitai cautions against the “schematic” solutions of populist politics (“we have a tsunami of these kind of characters”), preferring to tease out contradictions in the hope that they might reveal something significant.

Gitai is an impassioned participant in his interviews with powerholders – this is, after all, an emotional issue – but explains how he is keen to avoid the kind of hectoring adopted by Michael Moore (“at the end of [a Moore] film I feel I doubt ideas I think I support”). He reserves a much gentler interview style with the community members he meets, asking simply, often through interpreter, about their lives, losses, hopes and dreams.

Hope lies with several small scale NGOs that are seeking to bring communities together and shed light on tensions that need to be resolved. Gitai’s most strident note in the post-screening discussion is to speak in defence of their embattled public funding. For the architect student and army reservist turned documentary film maker, these are the real people seeking the real solutions: “I support all of them.. great people… they are courageous”.

“I was looking for every crack in the wall”

We see the Parent’s Circle, a group of women united in grief from opposite sides of the conflict: some losses recent and too raw to talk about, others more historic but no less felt. Together, they pursue practical work and gradually overcome their differences: “our tears are the same”.

Other inspiring examples are revealed. B’Tselem documents human rights abuses, Palestinian women learning from Israelis how to use their camera zooms to stay at a safe distance rather than dizzy the viewer. Breaking The Silence involves Israeli army veterans using their experiences to draw attention to the impossible contexts in which they have been asked to operate. Then, there are the rabbis working hard to protect a Palestinian village school in the midst of a settlement. Built out of passion from mud and tyres, the school makes a startling symbol of the need to overcome entrenched thinking.

One of the film’s most startling sequences comes when Gitai interviews a young Palestinian boy he happens to meet after filming a different setup. The boy wants nothing more than to be a martyr, seeing this pursuit of a ‘good death’ as preferable to a ‘good life’. After gently enquiring about his ambitions, Gitai leaves the boy with a simple admonishment to live rather than die well.

WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER documents the day-to-day goodness demonstrated by volunteers and community leaders. At the end of the evening, Gitai leaves us in no doubt that they are the future. The arts have a powerful role to play too, but they can’t remain depoliticised: “arts and the cinema have to re-engage with the reality – this is a civil gesture this film”. And it is these civil gestures that will lead to lasting change:

“In the far future – these women will have a memory of who gave them a camera.”

HUNGRY FOR MORE?

- Find WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER and Amos Gitai on IMDb.

- WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER received its UK premiere at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) on 23 NOV 2017. The film was introduced by Amos Gitai and Nico Marzano and followed by a conversation between the two.

- The film begins a regular run at the ICA.

- Nico Marzano is the Artistic Director/Founder of FRAMES OF REPRESENTATION, the festival of new directions in documentary.

Join the hunt for adventurous moving pictures.

SUBSCRIBE to get weekly GUIDES in your inbox (link below) and FOLLOW for daily recommendations on Twitter and Instagram.

Featured images: WEST OF THE JORDAN RIVER (2017).